The emotions of investing have destroyed far more potential investment return than the economics of investing have ever dreamed of destroying.

~John Bogle Founder, Vanguard Group

If you’ve been wondering about the book I wrote, RETIRE RESET!, we are publishing some excerpts right here on our blog so that you can learn more. Along the way, you will learn why our firm, Integrated Retirement Advisors, was founded: we’re on a mission to help people with retirement!

Here are some excerpts from Chapter 4.

Chapter 4: MINDING YOUR BEHAVIOR

My first stock market crash began at the opening bell. Recently minted, I was a “financial advisor” for just over a year when Black Monday unfolded. What a day October 19, 1987 proved to be. Starting in Hong Kong and blowing through Europe, a chain reaction of market distress sent world stock exchanges plummeting in a matter of hours. As described by Donald Bernhardt and Marshall Eckblad in their report to the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, there was no sanctuary. In the United States, the DJIA dropped 22.6% in one day’s trading, and over three consecutive trading days back then, the S&P 500 lost a combined 28.5% of its value.

I took calls that day from panicked investors who were in the process of moving their pension assets to my supervision. Unable to get through to their brokers with sell orders, they were seeking my assurance that all would not be lost forever. Of course, even if their brokers had taken their calls, the sheer number of sell orders that day vastly outnumbered buy offers anywhere near previous prices. That lack of liquidity—i.e., the absence of buyers—in the face of panic selling is what gave rise to the downward cascade in stock markets in the first place.

This crash was different because it was truly a global event. For the first time, it brought home to American investors—including many baby boomers entering their prime earning years and just starting to invest—the interconnected nature of markets around the world. Donald Marron, chairman of Paine Webber, a prominent investment firm at the time, underscored the new reality: “Nowhere is that (inter-relatedness) exemplified more than people staying up all night to watch the Japanese market to get a feeling for what might happen in the next session of the New York market.”

In retrospect, there was no need for panic. In fact, according to the follow-up Brady Presidential Task Force report, panic selling was estimated to have needlessly cost investors $1 trillion. But in the moment, facing a financial loss of unknown magnitude, fear overtook rational thought, statistical analysis, and probability modeling. Under severe stress, many investors tend to react irrationally—often to their own detriment.

Our Financial Ticks

Classical economic theory developed in the 18th Century proposed that human beings are rational, marginal-utility-seeking creatures who make financial decisions based on ice-cold calculation. But starting in the 1970s, a more contemporary school of economics emerged, focused on the study of measurable behavior when real people make real financial decisions. Working separately at Chicago, Princeton and UCLA, professors of psychology Richard Thaler, Daniel Kahneman and Shlomo Benarzi inaugurated the field of behavioral finance. Combining finance and behavioral science, its goal was to identify the emotional, psychological, and cognitive factors that shape real-time human financial choices in an effort to improve outcomes.

Kahneman recognized the roles emotion and intuition play in people’s decision making. He proposed a framework of “two minds” to describe the way people make choices: the intuitive mind forms rapid judgments without conscious inputs, and the “reflective mind” is slow, analytical and requires conscious effort. Aware or not of our cognitive biases, we are their prisoners. They’re like ticks. We have no conscious control over them. In fact, they control us.

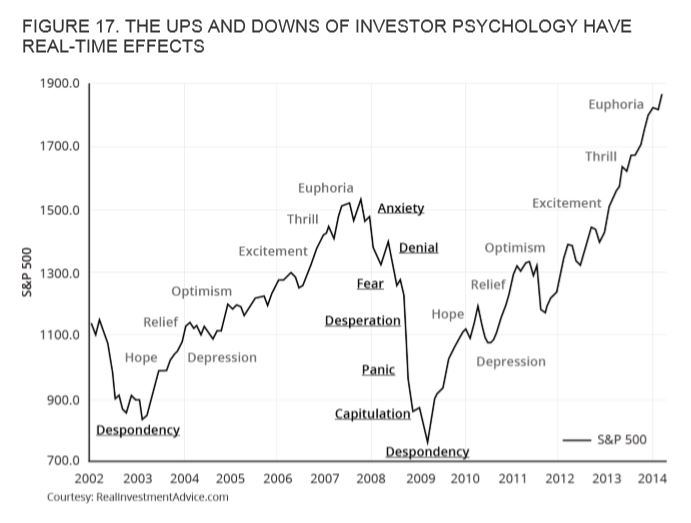

When it comes to our finances, fear of loss—loss aversion—is said to be at the core of our biases, dominating our decision-making and behavior. Scientific studies have shown that people display a hyper-negative response to potential loss in all its forms. Research conducted at Harvard found that for the average person, losses hurt twice as much as equivalent gains yield pleasure. Researchers at Columbia concluded that retirees are up to five times more sensitive to losses than the average person, so for the people reading this book, losses hurt ten times more than equivalent gains give pleasure!

At the other end of the impulse-spectrum lies greed, the human desire for “more.” In his 2004 Chairman’s Letter, Warren Buffett, considered an investment oracle, advised that “the fact that people will be full of greed, fear or folly is predictable” so if investors insist on trying to time their participation in equities, they “should try to be fearful when others are greedy and greedy only when others are fearful.”

This was Buffett’s acknowledgment that individual investors tend to buy high and sell low precisely because they follow the herd instead of taking a contrarian position. After loss aversion, herding is acknowledged to be the key bias at the root of average investor under-performance. Investors following the herd have historically bought high (out of greed) and sold low (out of fear).

FIGURE 17. THE UPS AND DOWNS OF INVESTOR PSYCHOLOGY HAVE REAL-TIME EFFECTS

Some academics argue that better financial education can enhance investor savvy and strengthen investor resolve to stay invested through market downturns rather than rush for the exits.

Personally, I suffer from a version of what I call “DM Syndrome’—of the magnification variety—and try as I might, I can’t shake it. Black Monday left an indelible mark on me. Knowing that the circuit breakers installed into the stock market’s trading rules after the 1987 crash only limit a one-day index drop to 20%, I ask myself every morning if this might be the day the unforeseeable bears down on us.

Apparently, I am not alone. Writing in the New York Times on Black Monday’s 30th anniversary, Nobel Prize-winning Yale economist Robert Shiller opined that “we are still at risk (of a repeat of the worst day in stock market history)…because fundamentally that market crash was a mass stampede set off through viral contagion…(reflecting) a powerful narrative of impending market decline already embedded in many minds.” In other words, the primary cause of Black Monday, according to Professor Shiller’s research, was not financial or economic in nature. It was a shift in mass psychology fed by rumors gone viral (and that was before we had the Internet to instantly transmit them around the world).

[Recent events in March 2020 have borne this out with the stock market downturn. The coronavirus outbreak is a prime example of a Black Swan—unforeseeable—event that should be mitigated by the retirement portfolio’s design.]

Unlike in 1987, today I am prepared. And I believe my clients are also better prepared to weather market uncertainty, extreme volatility and even a sudden shift in mass psychology. Because the FIA anchoring the stable-core portfolio helps insulate investors from market losses, it can obviate panic, mitigate fear, prevent needless selling, and thankfully, help avoid recriminations. Investors in the FIA-anchored stable-core portfolio can stay calm and clear-sighted, their reflective minds in better control over their intuitive urges.

Chapter 4 Takeaways

- The school of behavioral finance illuminates the complex inner workings of our minds when it comes to managing our money under both normal and stressful conditions.

- Individuals’ decision-making is influenced by built-in behavioral biases that often overwhelm rationality and thereby undermine investment success.

- When markets turn back, fear-driven loss aversion can distort rational thinking and test our resolve.

- The need for confirmation leads the average investor to buy high, while the dread of bottomless losses induces the average investor to sell low.

- According to research firm Dalbar, buying high and selling low is believed to account for the 50% return shortfall suffered by average mutual fund investors when compared to the long-term average performance of the funds themselves.

###

If you would like to discuss your personal retirement situation with author Nahum Daniels, please don’t hesitate to call our firm, Integrated Retirement Advisors, at (203) 322-9122.

If you would like to read RETIRE RESET!, it is available on Amazon at this link: https://amzn.to/2FtIxuM