by M. Nahum Daniels

If you’ve been wondering about the book I wrote, RETIRE RESET!, we are publishing some excerpts right here on our blog so that you can learn more. Along the way, you will learn why our firm, Integrated Retirement Advisors, was founded: we’re on a mission to help people with retirement!

Here are some excerpts from Chapter 6.

Chapter 6: WALL STREET INSECURITIES

“Unless you have millions and millions and millions … you cannot retire on the investment return on your savings … because there is no return on it.”

Jeff Gundlach, Bond King & Modern Art Collector, Founder and CIO, DoubleLine Capital

I first conferred with Mauricio in 1995, overlooking New York’s Central Park from a Fifth Avenue penthouse filled with modern art. Studying his experience as a do-it-yourself retiree has taught me an invaluable lesson: Even if you enter retirement with many millions, you are always subject to the risks, rules and ratios embedded in modern retirement planning. Should they go misunderstood or ignored, the result can be depletion and austerity—no matter how wealthy you may be starting out. Retirement success, on the other hand, especially if you have only modest wealth, depends on an informed approach to managing your nest egg that properly balances your capital and spending over an open-ended time horizon.

Do you find it hard to believe that even the very rich can run out of money? (Do you find it even harder to be sympathetic?) Allow me to demonstrate the vital lessons worth learning.

Deciding to enter retirement as he turned 65, Mauricio had just completed the sale of a Parisian fashion company he founded, clearing a nest egg of $100 million. Our purpose in meeting that day was to discuss his legacy planning. He faced a 50% estate tax upon his death and was looking for ideas that could mitigate the impact of those levies on his children and grandchildren. As for Mauricio’s income planning, he wasn’t looking for help from me or anyone else. He made it clear that he would consider only US Government bills, notes and bonds.

Mauricio, as it turns out, had serious trust issues. A Holocaust survivor, he spent some of his formative years in Buchenwald, the Nazi slave-labor camp near Weimar, Germany. At age 15, he was one of the prisoners liberated by American troops in April 1945. While maintaining his European connections and building a post-war business there, Mauricio became a proud and grateful American citizen, trusting in the inherent goodness and reliability of US government promises. It was simply unthinkable that the United States of America could ever default. In his mind, government paper was as safe as safe could be, and he viewed it as the key to a “risk-free” retirement that would let him sleep soundly at night while enabling him to live a fulfilling life by day.

And he wasn’t one to fuss. A saver at heart, he’d be happy to buy and hold US notes for their ten-year duration and simply roll them over to new issues when they matured. He would hear of nothing else. Risk was anathema. Professional advice was gratuitous. He would manage his own money by lending it (safely) to the US Treasury.

Besides, in January 1995 savers like Mauricio could still thrive. The risk-free 10-year Treasury note was yielding 7.69%. In theory, it would pay him annual interest of $7,690,000 for ten years without having to dip into principal. What’s more, that yield was tax-advantaged: Interest income on US Government obligations was then (and is still) given preferential tax treatment. He would have to pay about 40% in federal income taxes but would avoid New York state and city taxes that together could have easily added another 10% or so to the burden.

Mauricio estimated that around $4.6 million spendable dollars would enable him to fund his family needs and essential living requirements, his discretionary globetrotting, his passion for modern art and his generous philanthropy. So, he matched his lifestyle to the income his capital would generate. “Living off the interest,” he began his retirement by effectively withdrawing 7.97% from his nest egg. As for his estate-tax obligation, he would simply set up a life insurance trust and be done with it.

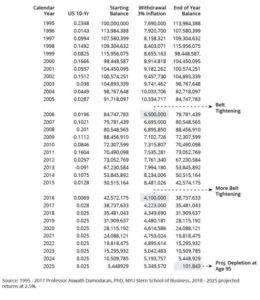

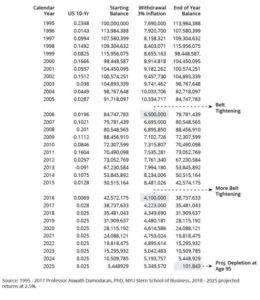

Later on, I learned that Mauricio had failed to factor in inflation, which averaged around 3% a year during the decade that followed (and even more in the prices bid for modern art). To keep up with his increasing cost of living he would have to up his annual withdrawal. To avoid dipping into principal, Mauricio faced the sacrifice of reducing his art-buying and charitable giving. He decided to give his lifestyle priority. Luckily, falling Fed interest rates during this period mitigated any capital depletion as he sold some of his bonds into a rising-price market. Still, after ten years, he found that he was left with only $85 million of the $100 million with which he began (Table 2).

When he rolled his portfolio over in 2005, however, 10-year rates on government notes had fallen to 4.16%. Reinvesting his capital at age 75, he would be earning $3.54 million in interest, less than half of what he had started with ten years earlier, and after federal income tax, it would leave just $2 million spendable dollars. Meanwhile, his annual expenses had inflated to over $10 million. Withdrawing $10 million a year from an $85 million nest egg would equate to a 12% annual withdrawal rate. Now 75, he wanted that money to last him another 25 years, just to be safe, and a 12% withdrawal rate would put him at great risk of premature depletion.

Facing the same challenge that can confront every retiree, Mauricio recognized that something had to give—despite the abundance with which he was blessed. He would either have to cut back his lifestyle or tap into principal and risk running out of money. He decided to reduce his annual withdrawal to $6.5 million. His art collecting slowed; his travels became less frequent; his charitable contributions less charitable. Bottom line: He started to feel pinched.

Despite the belt-tightening, at age 85 Mauricio found he only had $42.5 million remaining when the time came to replenish his matured portfolio with newly issued bonds. His luck couldn’t have been worse. It was January 2015 when the ten -year rate hit 1.81% and Mauricio had to face the reality that his remaining principal would generate taxable interest of just $766,000 each year! Still healthy and active, he found himself a victim of his own loss-aversion, severely set back by the Fed’s Zero Interest Rate Policy (ZIRP). His was an almost unbearable dilemma: Accept more austerity by further shrinking his lifestyle, family and charitable giving (and start to sell off his beloved art collection) and still face possible depletion at age 95—and/or chase higher yields by taking on more risk.

TABLE 2. MAURICIO’S SURPRISING RETIREMENT OUTCOME

A Shadow Banking Crisis

Mauricio’s dilemma is the same one that has faced all savers since the Great Recession of 2008 [and we are seeing it again now, during the current 2020 crisis]. Low yields pressure you to turn to a subset of “shadow banks” for greater returns.

Like the big commercial banks, the shadow banks are financial intermediaries. Unlike their commercial counterparts, they are not “cash depository” institutions; they are neither able to borrow from the Fed’s discount window in a crisis nor insure your account for up to $250,000. Some of the shadow banks—the ones of interest to us as investors—specialize in the issuance, custody and trading of non-cash financial instruments known as stocks and bonds. These institutions include the investment banks, broker dealers, money management firms, mutual fund companies and hedge funds that comprise the Wall Street community.

The Wall Street subset of the shadow-banking universe provides no guarantees. On the contrary, like commercial banks they commerce in risk—offering returns arguably great enough to compensate for the possibility of “capital impairment,” i.e., financial losses, temporary or otherwise. The Wall Street shadow banks earn money by exposing your cash to risk and trading their own.

Transforming Savers into Investors: [Stocks and Bonds]

When buying a bond, you’re lending money to a government or business in return for an interest payment over a given period of time, at the end of which you expect to be fully repaid. Like lending to a bank when you make a deposit, you are giving the borrower the use of your money for a price. Bonds come in a myriad of forms, offering claims against the borrower’s assets in the event of default based on the specific terms of the loan set forth in their respective indentures. If a secured borrower defaults, you may claim against its assets for repayment and you may come before other types of creditors. The less risk incurred in making the loan—i.e., the more credit-worthy the borrower—the lower the interest offered. When held to maturity, the interest payments over time comprise your yield. Their steady cash flow stabilizes their value, so in terms of price, bonds tend to be less volatile than stocks.

Buying a share of stock represents an incident of ownership, or equity, in a business. Stocks have no maturity date; you own them until you decide to sell them. Their payouts come in the form of dividends made at the discretion of management—both in terms of magnitude and periodicity. Some years you may get more, some less, and some none depending on the company’s operating profitability and other financial circumstances.

Among larger, mature dividend-paying US companies, dividends reflect about 50% of annual earnings. Dividend flow as a percent of the share price you paid is a critical component of stock ownership, sometimes amounting to 40% of the total return earned over time. But as an owner, you are taking the risk of total loss in the event of business failure because you are at the bottom of the capital stack, and lenders get paid first. Risk of total loss is balanced by the potential for greater reward in the form of price appreciation.

Company growth tends to be reflected in a rising share price, offering the potential for a gain on the capital you invested in addition to the dividend yield. These two components—dividends and gains—make up the “total return” potential of your invested capital.

Importantly, stocks tend to be much more volatile than bonds in terms of price.

The Wall Street brokerages buy, sell, hold and trade securities (including stocks and bonds) for their customers’ accounts. Wall Street dealers also own stock and bond inventories to facilitate customer transactions and earn proprietary trading returns.

Broker/dealers do both. The money center commercial banks, like Bank of America, have wealth management arms that are their broker/dealer affiliates, like Merrill Lynch.

Like the global economy, the investment business too is always evolving. Traditional stockbrokers can execute customer orders or make recommendations considered suitable based on their knowledge of the client’s risk tolerance, investment objectives and time horizon. Fee-based portfolio managers at mutual fund companies, money management firms, and hedge funds usually require a free hand to buy and sell securities on a client’s behalf, so handing over discretion to the portfolio manager is often mandatory. Commission-based brokers at the big bank “wire houses” and other execution-based brokerage firms typically require a client’s consent to a trade before its execution.

Trading for Trading’s Sake

With or without discretion and whether commission- or fee-based, the buying and selling of securities encapsulates the raison d’être of the Wall Street shadow banks, and securities trading is their lifeblood. But trading for trading’s sake tends to invite speculation and receives criticism from buy-and-hold investors who tend to be more analytical and systematic.

Beginning in the late 1990s, stockbrokers took on the title “financial advisor” when the big wire houses shifted from a commission- to a fee-based revenue model and wanted to exude a more knowledgeable, caring and comprehensive approach to customer service. Fees are a steady income source that levels out brokerage-firm cash flow, so most firms prefer them to the less consistent flow derived from broker commissions.

Trading is a win/lose proposition that pits buyers and sellers against each other, with both sides seeking an advantage. Buyers want to spend less and sellers want to get more for their securities. Traditionally, investment securities are valued—or priced—based on specific free -market fundamentals. For bonds, the key metric is “yield,” or the cash flow they generate. Yield translates into price: the lower the yield an investor is willing to accept, the higher the price that investor is willing to pay for a bond—the standard of “fixed income” investments.

Bonds reflect the forces of supply and demand in capital markets. If borrowing demand is high and money supply is low, the cost of money naturally rises and borrowers offer higher yields in the form of interest on the debt they issue. If money supply is plentiful and loan demand soft, lenders are likely to accept a lower rate for putting their surplus cash to work. In a free market, the forces of supply and demand naturally find equilibrium.

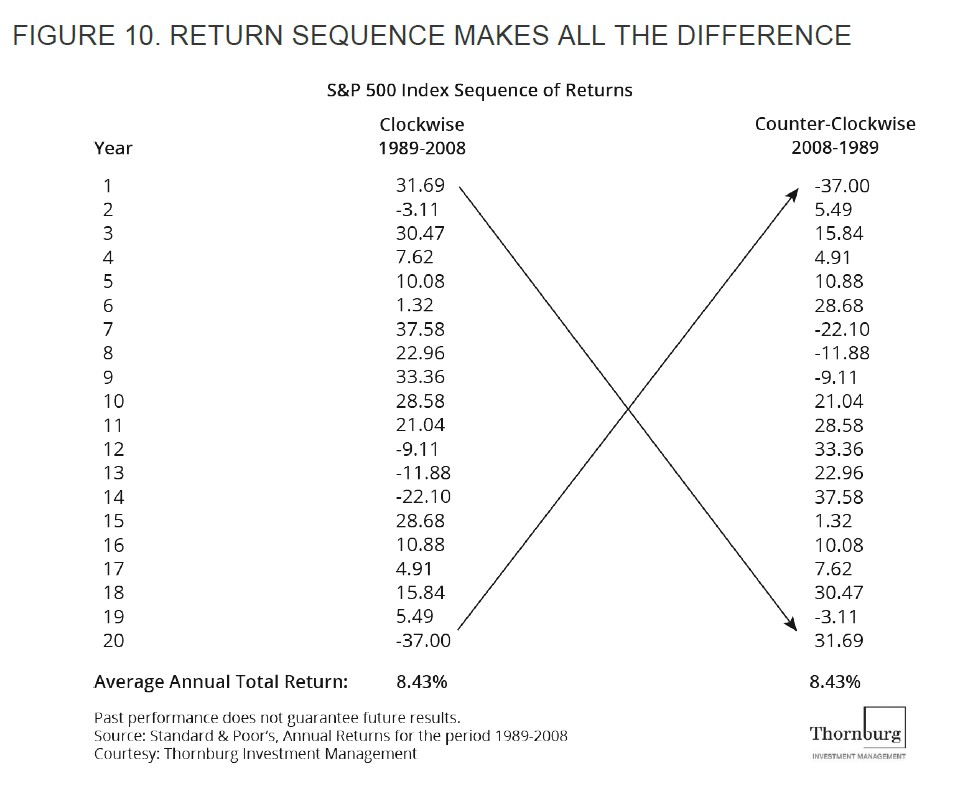

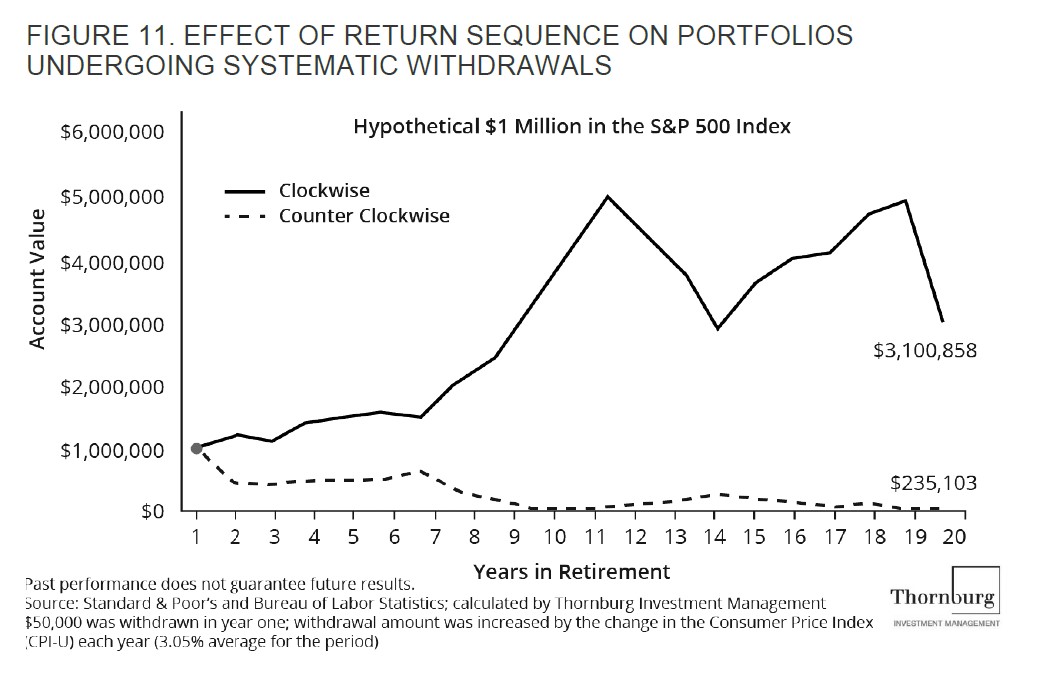

An important concept that retirement investors need to understand is that underlying Wall Street’s advice is a narrative that can give rise to exaggerated expectations and a methodology that can ultimately cause your undoing. Rather than buttressing the retirement process, the conventional principles of diversified investing, applied to retirement portfolios, may actually reduce portfolio reliability. Investing in securities at the wrong times and under adverse conditions can increase the odds that you run out of money; if you do make poorly timed decisions, then protecting yourself and improving your probability of success require you to self-impose austerity from the moment you start spending down.

The Wall Street Retirement Portfolio

The “balanced portfolio,” which can sometimes over-weight stocks and at others over-weight bonds, has become Wall Street’s signature retirement planning product. Applying Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT), it diversifies among stocks and bonds along an efficient frontier of return per unit of acceptable risk. A 60-40 stock/bond mix is deemed suitable by regulatory authorities for most individuals with median risk tolerance, so an advisor or firm can rarely be faulted for recommending it, even if an outcome falls into the rare extreme of return distribution. If the S&P 500 Index historically averages 10% growth per year and the UST 10-Year averages 5%, then a 60%/40% stock-bond portfolio can be expected to average 8% going forward, goes the oft-repeated incantation.

While the exact composition of each asset class may differ somewhat from firm to firm, most Wall Street customers end up with remarkably similar “investment policy” portfolios in terms of allocation, downside risk exposure and upside potential.

Projecting future returns based on historical averages is known as “deterministic” modeling. It is a form of linear forecasting wherein expected returns do not vary over time—and that’s its key flaw: the average return is most likely the one return an investor will never receive. Thanks to the increasing availability of computer power, “stochastic” modeling has grown in popularity. Applied to statistical sampling, stochastic modeling incorporates randomness. It has been tailored to retirement planning in the form of Monte Carlo simulations, named by one of its original developers after his favorite pastime—calculating the odds of winning at the casino.

In Monte Carlo computer software, returns and inflation are treated as random variables. Monte Carlo “engines” generate thousands, tens of thousands or even hundreds of thousands of possible combinations that produce a probability analysis, i.e., a statistical range of outcomes reflecting the financial impact of various return sequences. Now the standard retirement “modeling” tool, it perfectly captures the Wall Street approach to securities-based retirement planning by surrendering to uncertainty and accepting the necessity of playing the odds.

Changing the input assumptions and the type of mathematics used in a given Monte Carlo engine can materially alter the results. Critics focus on this subjectivity, which they claim introduces bias into the design. Mathematician and financial advisor James Otar, CFPTM, argues that the methodology tends to overstate the probability of favorable outcomes, giving clients a dangerously ex-aggerated sense of security.

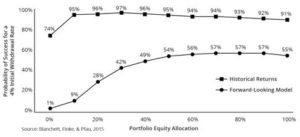

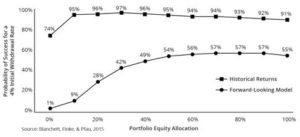

Leading researchers in retirement-income planning have recently published seminal studies that address these issues, with some surprising conclusions. Working together, professors Wade Pfau, PhD and Michael Finke, PhD, of the American College of Financial Planning, along with David Blanchett, CFA, CFP, head of retirement research at Morningstar Investment Management, tested the 4% Rule under historic return assumptions and then under forward-looking assumptions, illustrating the possibility of Shiller CAPE-based lower returns.

The group confirmed that based on historical data (stocks returning 12%, bonds returning 5% and a CAPE ratio of 16), a portfolio allocation to stocks of roughly 15% or more would have likely achieved a 90% probability or better that a portfolio would survive thirty years paying out 4% adjusted for inflation.

But if future expectations are lowered based on current interest rates (bonds at 2.5%) and the reduced stock returns predicted by today’s above-average CAPE ratio—even if lowered only modestly—the odds of success plummet, barely exceeding 50% no matter how high the stock allocation!

This industry-standard Monte Carlo probability analysis conveys a stunning implication: Using forward-looking assumptions, Bengen’s “the more stock the better” equity recommendation for portfolio reliability may be overstated. Given reduced future returns, it may even court disaster, driving the odds of 60/40 portfolio success down to 56%—or little better than a coin toss.

Figure 34. Projected Success Rates

Looking ahead based on lowered return expectations, Blanchett, Finke and Pfau questioned how a 90% (or higher) probability of portfolio success can be sustained. The answer: Only by reducing the [retrirement] withdrawal percentage in inverse ratio to the equity allocation; in other words, the higher the ratio of stock held in a portfolio, the lower the safe withdrawal rate you should use and the less income you should take.

Chapter 6 Takeaways

- Investing involves risk, including, in the worst case, a total and permanent loss of your principal. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Neither asset allocation nor portfolio diversification guarantee profit or protect against loss in a declining market. Bonds are subject to interest rate risks. Bond prices generally fall when interest rates rise.

- The projections or other information generated by Monte Carlo analysis tools regarding the likelihood of various investment outcomes are hypothetical in nature. They are based on assumptions that individuals provide, which could prove to be inaccurate over time. Probabilities do not reflect actual investment results and are by no means guarantees of future results. In fact, results may vary with each use and over time.

- It is advisable to understand the risks, rules and ratios embedded in the financial dynamics of modern retirement if you want to avoid failure—regardless of how much money you have at the start.

- Former Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke’s “new normal” of very low interest rates has turned many yield-starved savers into return-chasing speculators.

- Given current market valuations, the Shiller CAPE and other historical market metrics caution that equity returns over the next ten years or more may be lower than long-term averages might lead us to expect.

Questions for your financial advisor

- Do you rely on a Monte Carlo “tool” to project the probability of my (our) retirement success, and does that mean you can manipulate its mathematical assumptions to reflect better or worse outcomes?

- Do you counsel your clients to trust that the future is going to be rosy, or do you recommend they plan to withstand the worst while hoping for (and positioned to participate in) the best?

- If I’m nearing or in retirement, what initial withdrawal percentage would you recommend to set a floor for distributions from my nest egg?

- How did the balanced portfolio you’re recommending perform peak to trough, i.e., from October 2007 to March 2009?

- If we get a repeat of that performance at any time over the next ten years, what will it mean for my (our) withdrawals and standard of living thereafter?

###

If you would like to discuss your personal retirement situation with author Nahum Daniels, please don’t hesitate to call our firm, Integrated Retirement Advisors, at (203) 322-9122.

If you would like to read RETIRE RESET!, it is available on Amazon at this link: https://amzn.to/2FtIxuM

By Nahum Daniels, CFP®, RICP®

By Nahum Daniels, CFP®, RICP®